You are the one who holds with both hands the great sweet wort,

brewing with honey and wine.

Ninkasi, you are the one who pours out the filtered beer of the collector vat,

it is like the onrush of Tigris and Euphrates.

— The Hymn to Ninkasi

Depending on who you ask, early humans cultivated grain for beer before bread. No one knows exactly when or how we discovered fermented cereal could make us feel silly, but ingesting it became a priority once we did.

It’s possible that wild, airborne yeasts spontaneously fermented certain grains and an adventurous soul went ahead and ate them. If so — cheers to you, unknown tippler.

Whatever the origin, beer has been a big deal ever since. Long before people first contemplated fractions or figured out how to fashion a wheelbarrow, booze abounded. It was so important, even the gods got involved.

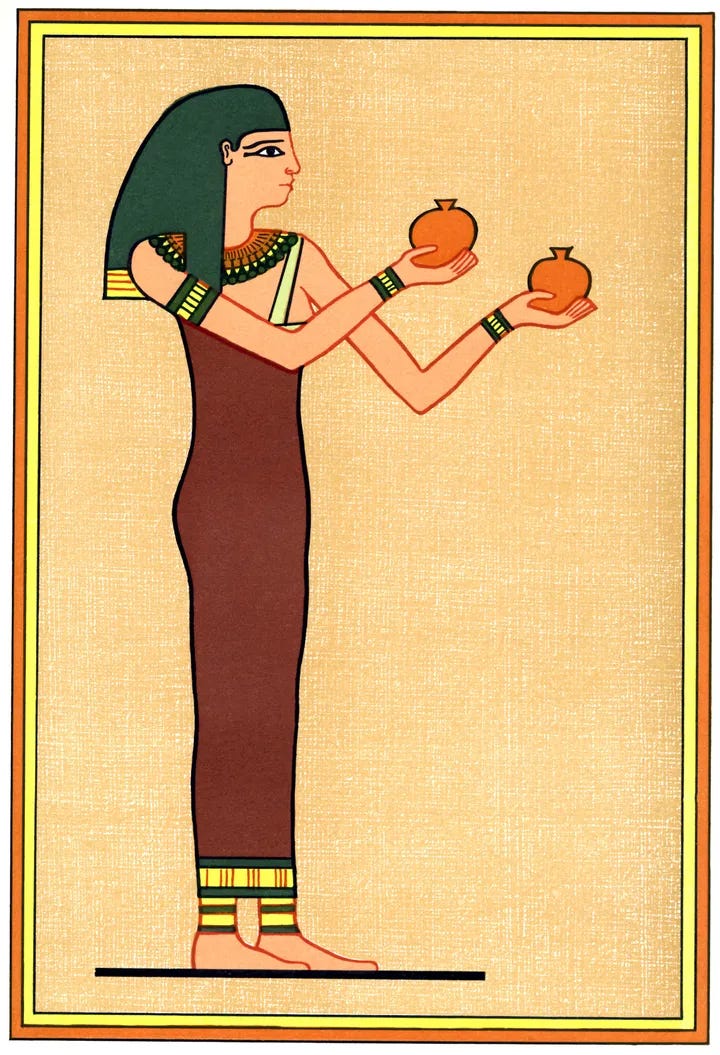

This helps explain why Sumer, one of the first civilizations in the world, called the mother of all creation Ninkasi.

Born of sparkling freshwater, Ninkasi’s job was to fill the mouth, satisfy desire, and sate the heart. She oversaw procreation, fertility, seduction, and war. She also happened to be in charge of brewing beer and did so daily.

The Brewess With the Best

Ninkasi bore nine children and named each one after an intoxicating drink or its effects. Naturally, that included “the boaster” and “the brawler.” The family called Mount Sâbu home, and from there Ninkasi oversaw the constant creation of fermented beverages to supply Sumerian temples with endless tipples.

Come spring, Ninkasi made the grain grow — a crucial staple at the heart of many a Sumerian ritual. In the ancient drinking song A Hymn to Ninkasi, Sumerians regaled listeners with one of the oldest brewing recipes recorded. The song also waxed poetic on this most sacred of drinks, and how it provided a joyful mood and happy (notice they didn’t say healthy) liver.

Safe to say, beer and bread were always on the menu.

From Ninkasi and various other supernatural mothers of things bubbly and bliss-inducing, legions of ladies continued the brewing tradition for hundreds of years.

Alewives International

Brewing routinely fell to the fairer sex in cultures worldwide, from Babylon and Taiwan to Japan, Colombia, Scandinavia, and Tanzania. People viewed it as an extension of cooking, baking, hosting, and keeping the home — all things women were pro at.

It seems natural that women — who were responsible for creating life — should create the food and drink that sustained it. That deities associated with brewing across the globe were linked to fertility was no accident.

That included Ninkasi and many more. Egypt’s Menquet and Tenenet, Mexico’s Mayahuel, China’s Yi Di, Zulu’s Mbaba Mwana Waresa, the Baltic’s Raugutiene, and Finland’s Louhi are just a sampling. In their image, earthly brewers mashed their hearts out to make grog, honey mead, boozy chocolate, pulque, and beer and wine hybrids. Oh — and don’t forget rice grain alcohol, barley bread beer, fermented sorghum brews, and lord knows what else.

They put their hands and mouths to work, chewing maize, cassava, quinoa, and rice to break down the starch before fermentation. Women brewed for ritual and religious purposes, drinking in the home, entertaining, and even commercial sale on a small scale.

In traditional Germanic societies, brewesses were responsible for preparing ale made from fermented honey. Even when the monasteries began to take over, there were still nuns among the monks who tinkered with tipples.

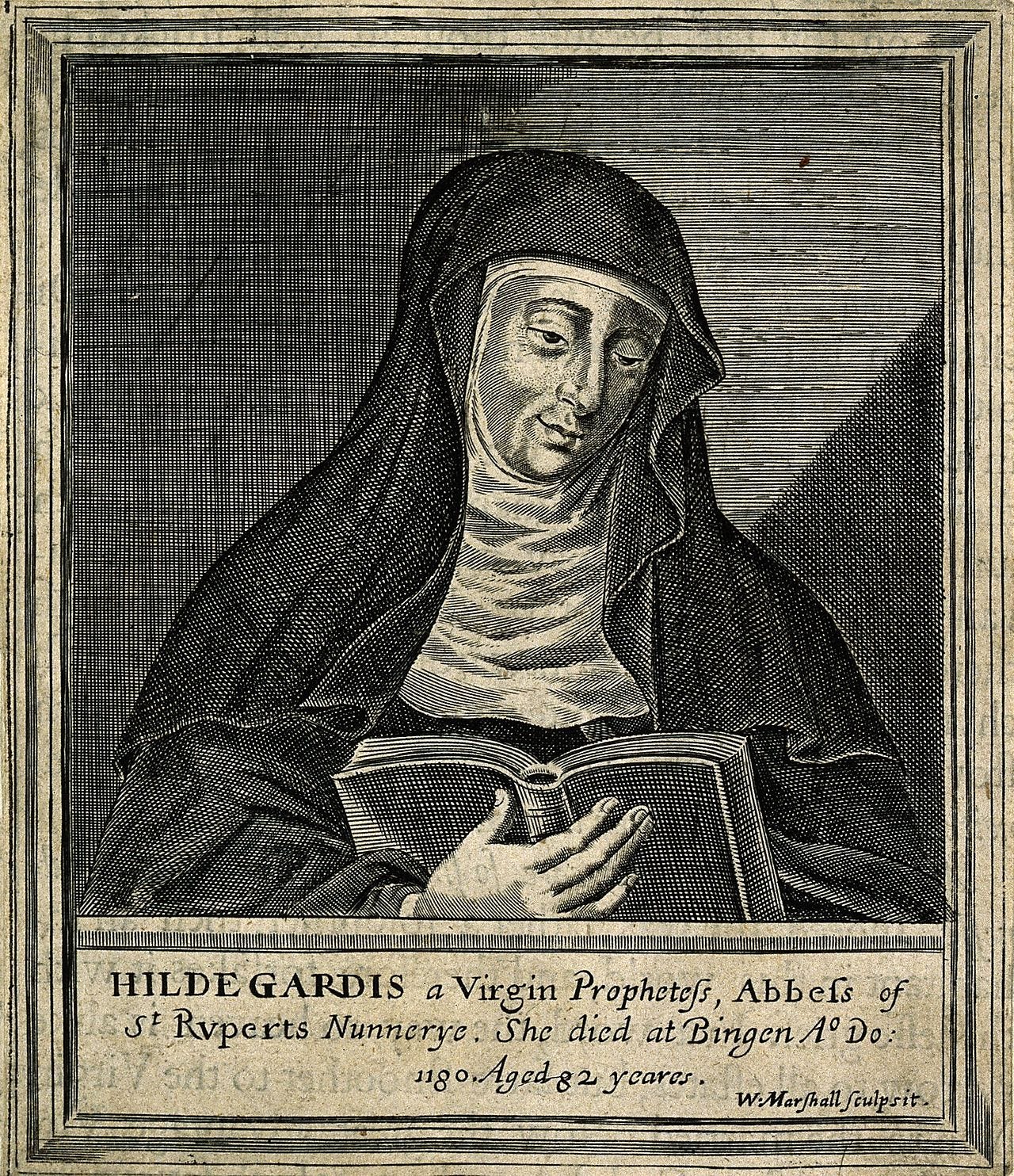

And if you love hops, you can thank St. Hildegard of Bingen, who documented their first use as an additive. Although Hildegard wasn’t a fan — she said hops weighed down your innards and made you sad — they prevailed in the end.

(Fun fact – Henry VIII shared Hildegard‘s distaste for hops. He even instructed the royal ale brewer never to use them.)

Hops make a solid preservative, so having hoppy beer on hand was key to staying hydrated when water was scarce. Even without hops, you could rely on beer to be safe thanks to the fermentation process.

Because home-brewed ales usually had a low alcohol content, they were readily consumed by nearly everyone in society.

Turning a Profit

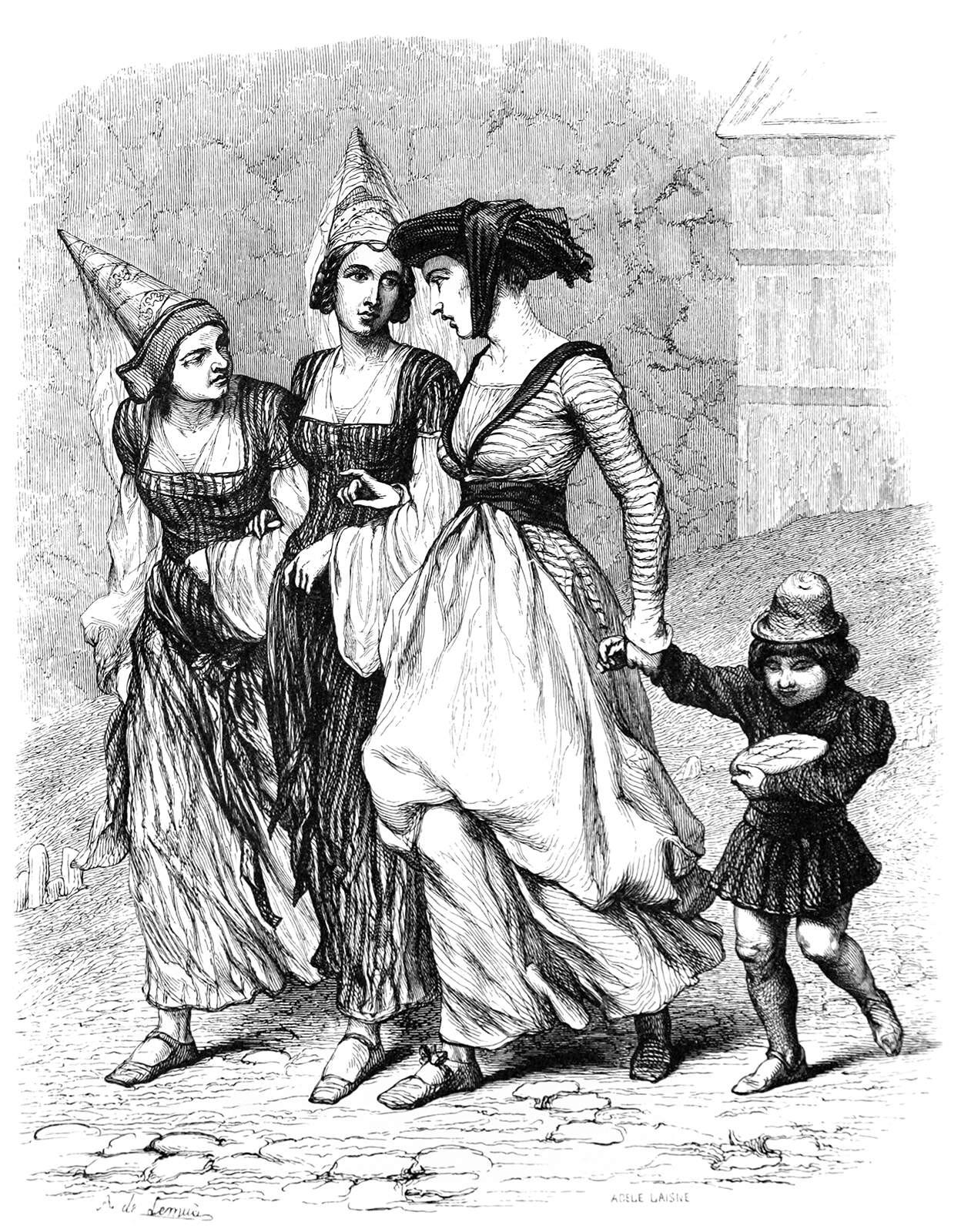

Brewing is a labor-intensive and time-consuming process, especially when you’re already tasked with maintaining the home. Many early medieval women worked smarter rather than harder, forming networks within the town to lighten the load.

It wasn’t uncommon for alewives to sell their extras to other families or private buyers. It was the perfect side hustle.

If she had the space, an alewife might invite paying customers into her home. And if she was really ballsy, she’d make it a full-time job.

The art of brewing and selling ale — adorably called tapping and tippling — made a lucrative career for some. It was one of the more stable, less degrading trades a woman could undertake. If she was business savvy, an alewife could make a solid profit, achieve social standing, and gain a little independence.

But! There’s always a but — your experience was heavily dependent on your marital status.

Miss Independent

As a widow, single mother, deserted or deserting wife, or just plain ol’ single lady, supporting yourself was extremely difficult. Unless you got into brewing!

You could see why selling ale was a tantalizing choice between marriages, during widowhood, or when poverty struck. You could take it up temporarily, didn’t need schooling, and paying customers were everywhere.

While you wouldn’t make the same amount a married woman would make with her husband, you could still scrape by in relative comfort.

That’s not to say it wasn’t a pain to tipple. Without backing or legal standing, an unmarried woman needed to brew and sell out of her home. As you can imagine, inviting alcohol-craving strangers or acquaintances into your home could be sketchy, so many women sold in public and stayed on the move.

Back at home, there weren’t usually many family members around to help and these gals couldn’t exactly afford servants. These obstacles made it extremely hard to scale the business or sustain it long-term.

The part-time status, lack of capital, and ever-changing selling locations also made an unmarried brewster’s operation seem suspect, especially when compared to more legitimate businesses. Over time, this bad reputation got worse, making it even harder for single alewives to keep on and carry on.

By the 1600s, most threw in the towel and tried getting jobs in brewhouses run by men. But like any group of people, a few figured out ways to game the system.

A tiny percentage of unmarried women managed to keep up the trade, with some widows and single women even enjoying membership in guilds like the London Brewers Guild. Fancy that.

Married to the Job

While marriage could be a crapshoot for women in the Middle Ages, there were advantages to having a husband. Married women often brewed in tandem with their husbands, acting as more or less equals.

Having a husband opened up a world of opportunities. The brewster had better access to capital and hired help, a representative in polite society, the might of guild membership, and respectability. No one accused a married woman of being sketchy unless they wanted to deal with her husband.

Before brewing became more commercialized around the 16th century, husband and wife teams split the labor down the middle. Brewing itself was relegated to the wife, who acted as management and oversaw the brewing process, directing servants, and managing the alehouse if they owned one.

The husband took on public-facing responsibilities, like attending guild meetings and taking care of legalities. But even when it came to guild activity, the wife still participated. Alewives often paid hefty guild taxes separately from their husbands, an indicator of equality in the eyes of the guild as well as a high profit attributed solely to the wife.

Last Call, Ladies

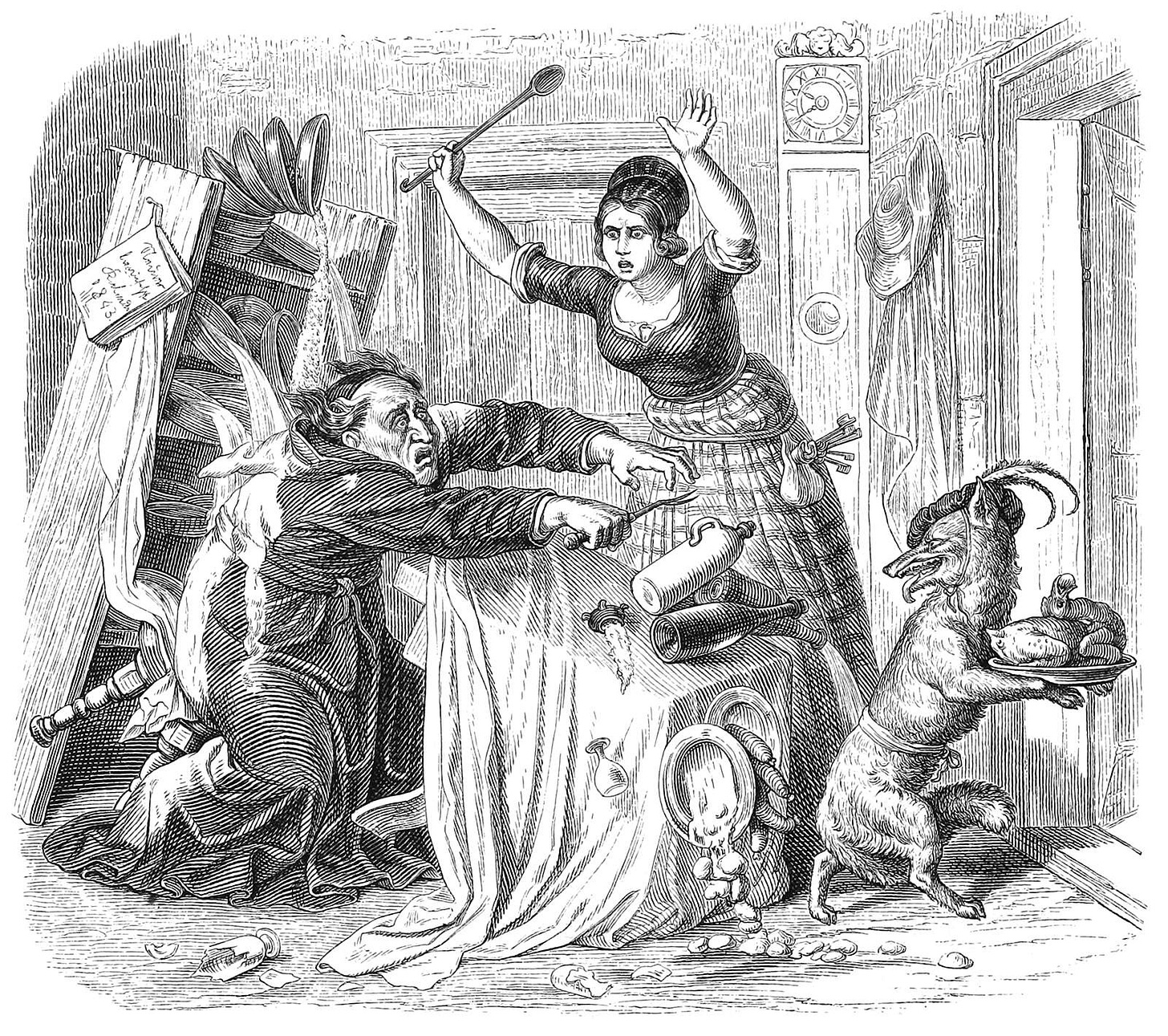

Brewing wasn’t all hops and happy hiccups; there were downsides too. Putting aside the fact that it was hard and repetitive work, brewing also put women in the crosshairs of men and the Church.

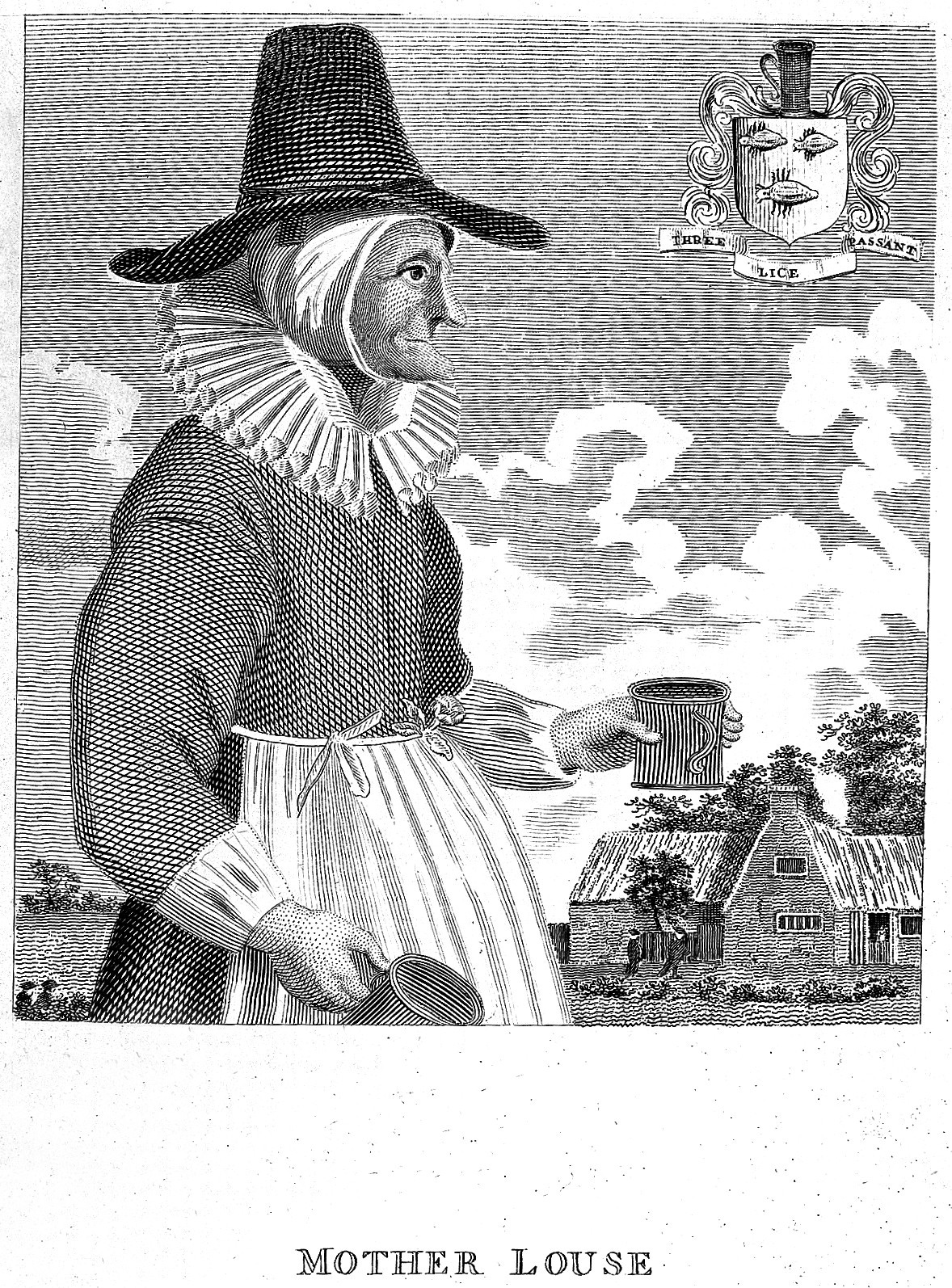

After the Norman conquest, domestic brewing in Europe picked up steam. Aristocrats hired alewives to make beer for their families (including men of the chapel and children). Women ran taverns that served a variety of concoctions, with some lauded for their “noppy ale,” like English brewster Elynoure Rummynge.

People also gossiped that Rummynge possessed a “hideous visage,” just in case she got too confident.

As brewing shifted from an in-house affair to a commercial one, men pushed alewives out. One of the main ways they did this was through those aforementioned guilds.

Guilds were essentially clubs anchored around different trades that sprang up in the Middle Ages. There’d be a baker’s guild, a tailor’s guild, a butcher’s guild, you get it.

The idea was to form an association that merchants or craftsmen could rely on for protection, mutual aid, and enforcement of quality and fair pricing.

Women were generally not allowed to participate in guilds, although some places allowed widows to inherit membership from spouses (yay, Netherlands!). But while brewer’s guilds took over ale production for the military and royalty, women still did their thing in the country.

There’s even evidence to suggest that within guilds the member’s wives were still doing a lot of the work.

Witches Brew

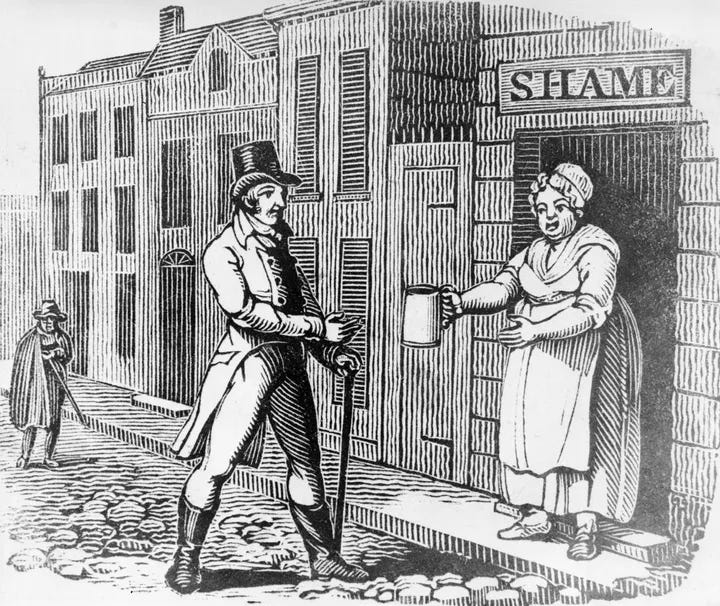

Another approach for kicking girls out of the club was plain old smack-talk. Negative sentiment about alewives was everywhere, with naysayers likening them to dirty old crones and grifters. While both genders engaged in trickery like serving watered-down ale, inflating prices, and robbing drunk customers, women shouldered most of the blame.

It’s an easy assumption to make when you believe women are naturally prone to wickedness and deception. That’s all down to a gal you might have heard of called Eve. Her infamous apple incident allowed the Church to claim that alewives couldn’t be trusted and that alehouses were a veritable playground of sin.

Powerful people used varying methods to keep these deviant brewsters at bay. For example, the city of Chester prohibited ladies between the ages of 14 and 40 from selling ale. That way, only women too young or old to be considered “desirable” could do so.

Representations in culture also painted ale-selling ladies as gross, sexually promiscuous weirdos. Popular poems talked of alewives who hired prostitutes, lured men away from mass, and…made ale with their noses.

Finally, the Church got artsy, creating murals and Dooms which featured alewives burning in hell. Subtle.

The Nail in the Coffin

As the industry became commercialized, many single women vanished from brewing while married alewives saw their roles change to a more informal one with less authority. After the 16th century, you’d often find her in her husband’s alehouse pitching in, serving, or acting as an unofficial manager.

Sensing they had a lucrative industry on their hands, men saw the promise of taking ale to the mass market. What was once a casual home-brewing operation dominated by women became a male-managed trade. It was increasingly impossible to bust into the business unless you had money and a guy around.

But hey, someone’s gotta bartend.

Sources:

Craft Beer & Brewing. The Oxford Companion to Beer Definition of Ale-wives.

Corran, H. S. A history of brewing. David & Charles PLC, 1975.

Protz, Roger. Great British beer book. Impact Books, 1997.

National Women’s History Museum. Women and Beer: A Forgotten Pairing.

Bennett, Judith. Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England. Oxford University Press, 1996.